Greetings, travelers,

But for family, I wouldn’t have been at the Riverwalk. After all, I don’t really like people, and so am usually alone in the mountains. I do come here to ski, but generally park in a buddy’s driveway and hike through the woods to the lifts. Still, it was fun, hanging out with so many members of my class, doing things I guess affluent people do when they are on vacation. I don’t really work, and by the same token don’t really have vacations, so I’m guessing.

This view reminds me of Seurat. (As usual, please use a big screen if you can.) You know the painting: A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, at the Art Institute of Chicago. The resemblance isn’t formal, of course, but sociological, and perhaps more deeply, psychic. Perhaps one cannot be better situated than to be a member of the haute bourgeoisie? More power is dangerous, mind bending. Fewer resources compromise autonomy. Maybe this is as good as it gets? Watching kids play in the water, listening to the summer orchestra rehearse? Just a thought.

I know, the hanging basket of flowers, which was what first caught my eye, are too strong. (Flowers probably grown and basket made in Alma, the highest town in the continental U.S.) Although, for that matter, the bustle in “La Grande Jatte” is too big, too. But I wasn’t thinking about 19th century Paris when I took the image, at least not clearly. Mostly I thought the flowers, then the broader scene, was pretty, rich, so I “captured” it, and hustled to catch up with my family. I flirted with driving back a few days later, trying to compose the image a bit more in line with my sociological musings, and fix the problem of the too demanding hanging basket. But it was a drive, other things called, and making the image so much more intentional might not have made it any better. We will come back to the notion of what used to be called a “snapshot” below.

With difficulty, in this Signal I’m not going to write about the election. I have somewhat mixed feelings about this. (“Mixed feelings,” you? Really? Again? Can’t you ever make up your mind? It’s tiresome.) It’s not that I have nothing to say. I’m sliding towards a book on the collapse (too strong?) of Enlightenment political ideals across the political spectrum and the North Atlantic. But there is too much noise, too little language with which to engage the emergent reality And, as I’ve tried to suggest, all this noise can be unhealthy, is unhealthy for friends and family of mine. I should hold my piece on these matters, and I am, for now anyway. The problem, for me, is that writing is much of how I think, which is how I cope. Well, one of the ways. And I’ve been thinking about the meanings of contemporary politics when our grammars fail for a long, long time, and feel a sort of psychic pressure to organize it, to make it all make sense, to find the ground on which I stand, and get everybody else to think right while I’m at it. So, my instinct is to write. But that will be another burden on me, and add to the noise . . .

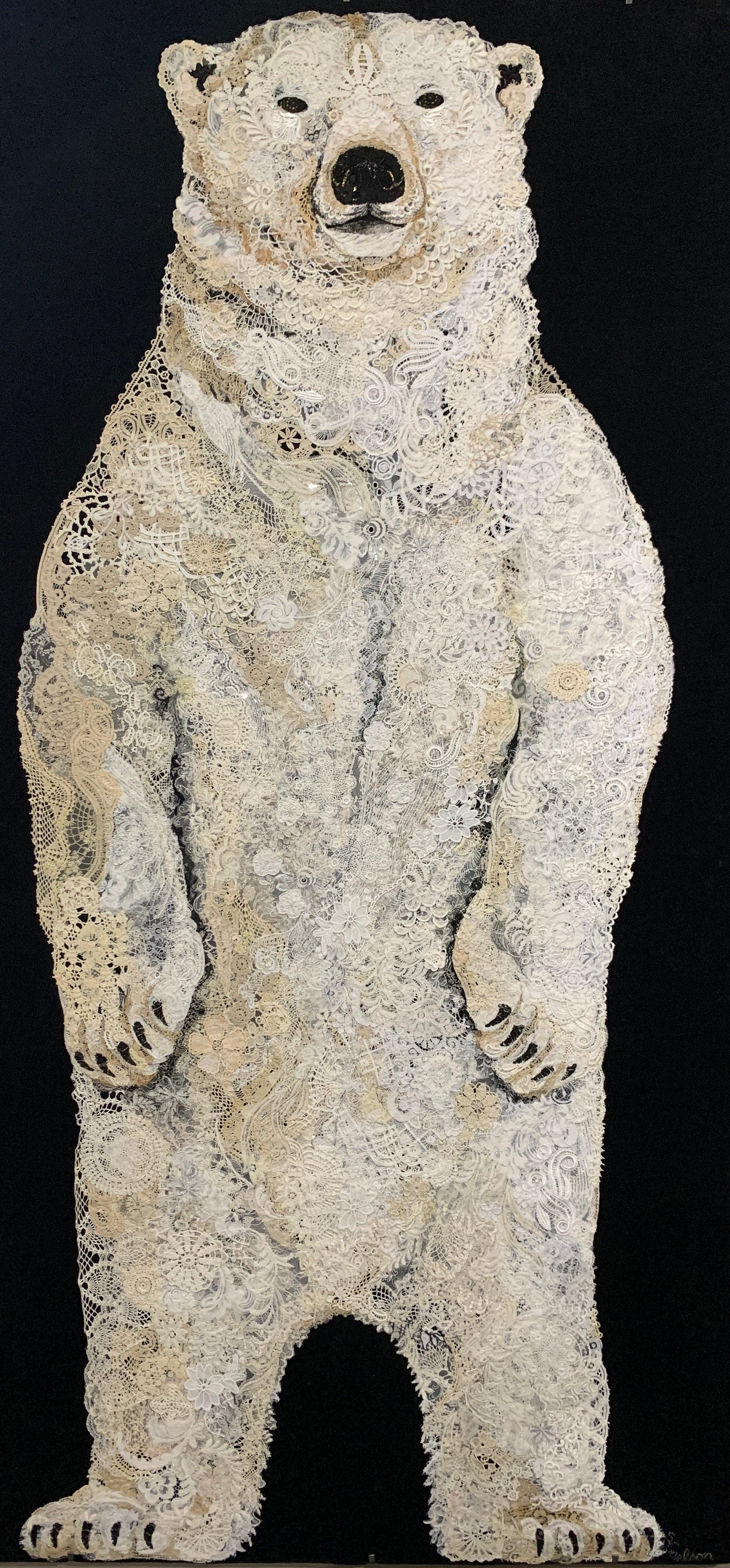

Quilting as Painting

The National Quilt Museum (NQM) is a capacious new building by the Ohio River’s levee in Paducah, Kentucky. Highly recommended. The quilts are stunning, and interesting, though I have my doubts, hence this little essay.

As one might expect from the name, quilts, most bright and some enormous, are displayed in well-lit, climate-controlled conditions. Well written placards discuss the provenance and sometimes the techniques involved. Despite the name, however, the place is more of a gallery than a museum, looking forward, not back. There are few if any quilts more than a few years old. I heard a member of the staff tell another visitor, “As you can see, we want to show that quilts are art, not just a craft.”

My first reaction – I think everybody’s first reaction – was “that cannot be a quilt, that’s a painting.” On close inspection, however, one sees that the images are constructed solely from colored fabric. That seems to be the cardinal rule: no painting on fabric. Just “painting” with fabric, or even thread. From its design to its texts to the words of its staff, the entire Museum expresses the aspiration of at least some quilters, and the Museum itself, that quilting be seen as, treated like, paintings. And the visitors say, keep saying, “it’s just like a painting.”

As I said, the quilts are literally stunning, but largely because, hey, they’re like paintings, but they’re not paintings! I spend a lot of time looking at paintings, even have a MoMA membership, so I know the drill, but I was slack-jawed for a few minutes at the NQM. This “gee whiz” response drives a painter friend of mine crazy. If people want to paint, they should paint. He finds the quilts “totally uninteresting.” And I have to say that I found few of the quilts all that compelling as paintings, or perhaps as the sort of paintings one used to see on the side of vans, garish, sometimes kind of beautiful, fun. Or the illustrations in children’s books, which can also be artful, as any parent who has re/re/re/read a book to a child might have reason to know.

The painterly quality is largely a function of the detail, as I hope to have illustrated here. Without work, the eye does not see the fabric, and certainly not the threads – it all blends into an image that is clearly not a photograph, so it must be some kind of painting. Something like that. Interestingly, the detail is not achieved entirely by hand. Almost all (all?) of the quilts I saw were stitched on digital sewing machines. While I don’t understand the process well, much of the artistry lies in the design and construction of the piece, which is then sewn.

I am reminded of Victorian architecture, which we tend to see as “handmade” because it is not “modern.” (I used to own a Victorian house.) In fact, the curved carpentry that characterizes Victorian architecture was largely the product of improvements in milling. Earlier eras could build things out of elegantly curved wood, but they tended to call that furniture. Older houses, even fancy ones, tend to have far straighter lines, easier to cut.

The NQM clearly distinguished between art and craft. These were items made to be looked at, admired, not used. Not a bed in sight. And just as clearly, the NQM privileged art over craft. These women (mostly) wanted to be seen as artists, not craftsmen or, heaven forbid, seamstresses or some such. There are rankings, after all.

I get it. But craft seems pretty important to me, too. One needs a bedspread, something to keep warm at night, and a traditionally American answer was a quilt. And quilts, most traditionally, were made from scraps of cloth that would otherwise be thrown out. Reuse, recycle. My mother made quilts. There was nothing like that at the NQM.

I will go a step further. Many people have little appreciation for art; deep appreciation is really difficult. And even those who do appreciate art deeply may not have the energy to do so every day, all the time. I’m fascinated by serious artists who owned serious paintings. Both Picasso and Matisse owned Cezannes. The mind boggles at the intensity.

But life also requires the ordinary, and it is nice when the ordinary is also good, made with, well, craft. As Wessie du Toit points out, one of the things hindering the construction of good contemporary housing in the U.K. is the unpleasant fact that are few people who have the skills to do the building. The Pathos of Things. Design alone is not enough. More generally, I wonder if part of the tawdriness of so much of our material world can be traced to the privileging of art over craft, or to put it the other way ‘round, the denigration of craft. So we live with a lot of junk.

Notes on Bad Photography

As you probably know, Colorado is dramatically beautiful. An old Kansas line: “Anybody can love the mountains. It takes character to love the plains.” Beauty can be found pretty much anywhere. But in some times and places, you have to work to see it, and in others, like the mountains of Colorado, beauty hits you over the head. Which is to say that Colorado mountain towns are pretty much ground zero for bad photography. Maybe Hawaii is worse, and there must be other places. I don’t know – it would be a fun parlor game: which place inspires the most bad photography?

I’m having fun, sort of. But it is difficult to enter a restaurant or other place of business hereabouts without being assaulted by a lurid photograph. It would be cruel to provide examples, but you know the kind of photograph I’m talking about, let’s call it “Mountain Beauty.” The image is almost always highly symmetrical. The colors are intense, punched up, which makes the light wrong. A buddy of mine, a truly good photographer, rails against such “post capture manipulation.” And the entire image is highly defined. It takes equipment and skill to achieve such definition, and possession of both is demonstrated. That’s how you know the photograph is “professional,” a word that also means “done for money.” Indeed, these pictures are done under the aesthetics (and so the ontology) of advertising. And people look at “Mountain Beauty,” often an image of what they have just seen, and say “look, how pretty.”

One must keep perspective, as it were. There are many things worse than bad, or just banal, taste in photography. But considering how much time we spend looking at images, it makes some sense to cultivate an aptitude for seeing, to use old fashioned words. So, what is so wrong about “Mountain Beauty”? What is so wrong about post-capture manipulation?

Such questions hinge on usually tacit understandings of photography, what photographs are, in some deep sense, as distinct from other kinds of images. How is a photograph different from a painting? (Different from a quilt?) As an aside: of course there are different kinds of photographs, but I think you know the sort of photography at issue: the perfect image that is produced in order to be admired. Mountain Beauty.

One place to begin is naively: “the photograph captures reality.” This is not true, or not simply true. The camera “sees” things differently than the eye. Without considerable effort, views of mountains, or flowers under trees, are represented as distant hills and sparks of color. We see not just with our eyes, but with our minds, which flip the images on our retinas, synthesize what each eye sees, and also edit, emphasize some details and suppress others, and so forth.

More to the point here, for over a century, photographers argued that what they were doing was not just reporting on reality, but making art. (Again, the desire to be seen as an artist runs deep in our culture. I feel it, too.) Digital cameras, to say nothing of editing software, are continuously “improved” by the addition of functionality that allows the [photographer] to edit the image in new ways. It was commonly said, in the early days, that photography would replace painting. It now appears that serious photography aspires to the condition of painting, the production of images as intended and controlled by the artist.

And so, through post-capture manipulation, e.g., by using Photoshop, the image is improved. The wisp of cloud is removed, the sky’s blue darkened, the definition of the foreground sharpened beyond that capacity of my eyes anyway, and so forth. “Mountain Beauty” is more “beautiful,” more “perfect,” than the mountain it ostensibly re-presents. Meretricious.

As already suggested, this aesthetic is familiar from advertising, which represents objects as desired things in order to encourage purchase. Economically, advertisements are not about what the viewer has, but what she might be persuaded to want. The image, then, is commonly said to be “flattering,” as opposed to true. So, the wisp of cloud is removed, the sky’s blue darkened . . .

I’m not entirely sure why people want to see nature, or pretty much anything, as advertisement. I think it is vanity, of the sort that informs Instagram and so much social media. Isn’t it cool that I’ve been here, aren’t you jealous? Human, all too human, and I’m guilty of that, too. But perhaps art requires a degree of what we pejoratively call vanity, more charitably self-expression? A desire to impress one’s fellows now, certainly before leaving?

Confessions aside, there is another way to think about photography, another aesthetic. In a once very influential book, On Photography, Susan Sontag wrote that photography was still a physical record of a particular place at a particular time, when this light hit those chemicals and reactions occurred. (At least I think she did, should have anyway, I read the book decades ago and don’t have it with me.) The photograph, as representation, does not “capture” the reality that the eye sees, but the photograph, as object, is a reality, and a reality that is specifically located in a time and space, is situated as is the photographer. Not objectively, of course, photographers frame and otherwise set up images. None of us are Ansel Adams, but Adams really was in the Sierras when the sun came up. In this view, photographs are physical artifacts of a time and place.

Digital photography made a mockery of this idea of physical specificity, because each pixel can be altered. Taking the photograph, the moment of “capture,” is merely the acquisition of raw data that can be manipulated by the photographer. In case the point was not clear enough, artificial intelligence uses huge troves of images to generate new images that need not represent any person, place, or thing at all. There are no proper nouns in AI, just data all the way down. (And now the data is increasingly corrupted by the profligacy of AI itself, but that’s another story.) In advertising, however, reality is hardly the point.

The fictional quality of AI images raises an important point. Like word writing, light writing (photo – graphy) need not be tethered to the material world. One may “paint” with pixels. Digital art need not represent any tangible thing, and is often fantastic, about a fantasy. Sometimes the intentions are artistic, but the affinity between fantasy and advertising cannot be gainsaid. One more purchase to make me happy . . .

Sometimes, however, we do want to address the world, rather than our desires or even our ideals of perfection. What I’m trying to suggest, what the existence of AI imagery helps us to understand, is that photography should attempt to convey the specificities of an experience. Although digital photographs are not artifacts like chemically produced images are, we should nonetheless treat our images as witnesses. Doing so might help us appreciate the condition of some human at some moment, just a photographer, but maybe we can imagine ourselves similarly situated, wondrous at the appearance of this, here and now? From this vantage, we can see the ethical/artistic temptation of post-capture manipulation: the photographer so easily moves from emphasis (unavoidable from the framing of the shot forward) to exaggeration, to outright deception, lying. That’s not how it was, the thoughtful viewer says. Just another pretty advertisement. But photography, at least the sorts of photography one should be doing while wandering about the mountains, is an occasion for existential meditation.

On a cheery note, Intermittent Signal is now read in 71 countries. Those of you with friends in Central Asia, much of Africa, island nations, or Vermont (?), are encouraged to share!

Enjoy the rest of summer.

— David A. Westbrook

Good to read, as ever, David. The reference to denigration of craft made me think of Ruskin. For example -

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/35898/35898-h/35898-h.htm

"I said, early in this essay, that hand-work might always be known from machine-work; observing, however, at the same time, that it was possible for men to turn themselves into machines, and to reduce their labor to the machine level; but so long as men work as men, putting their heart into what they do, and doing their best, it matters not how bad workmen they may be, there will be that in the handling which is above all price: it will be plainly seen that some places have been delighted in more than others—that there has been a pause, and a care about them; and then there will come careless bits, and fast bits; and here the chisel will have struck hard, and there lightly, and anon timidly; and if the man's mind as well as his heart went with his work, all this will be in the right places, and each part will set off the other; and the effect of the whole, as compared with the same design cut by a machine or a lifeless hand, will be like that of poetry well read and deeply felt to that of the same verses jangled by rote. There are many to whom the difference is imperceptible; but to those who love poetry it is everything—they had rather not hear it at all, than hear it ill read; and to those who love Architecture, the life and accent of the hand are everything. They had rather not have ornament at all, than see it ill cut—deadly cut, that is."

The George Washington University in Washington, DC houses the National Textile Museum. For years, I have known of this museum, one of countless others in Washington, but affirmatively had little or no interest in entering it. Then, a few months ago, my college alumni chapter arranged a tour of the museum (the director of which is an alumnus of my college). To my surprise, the displayed textiles were works of art as well as craft. They were beautiful and quite interesting too. I realized that my bias toward “beauty” and “artistry” and actually against seemingly “mundane” textiles had ignorantly deprived me of experiencing (and admiring/appreciating) the creativity expressed in the design and craftsmanship of products (mostly useful) made of thread. [This experience was a recent bonus of the liberal arts education I had the privilege and opportunity to be exposed to decades ago.]

The quilts made by members of my family are interesting as well as beautiful and functional. They also are part of interesting stories. A museum of storytelling, as well as interesting and beautiful, quilts would be a great place to visit.