Dear Pilgrims:

The news inclines me to take stock of what I have and have not done intellectually. My stance has always been one of loyal opposition, both supportive and critical, in short, apologetic. Our world is flawed, even fallen, but worse fates are easily imaginable, and perhaps we might, with care, do better?

Walking yesterday afternoon, coffee poisoning, too much to do, I hurriedly pass an old man coming the other way. Out of the corner of my eye: grizzled, Black, cane, zip up sweatshirt, hunched back, no threat, mumbling something about a little money for food. I spend a lot of time in the City, so of course I ignored him, no eye contact. A few paces on, though, my feet stop. Am I some sort of monster? Usually, yes, I guess so. I go back, hail him, give him some money, hurry on. At the edge of tears, but also deeply angry, rage at pathos, his/mine/ours, almost at the edge of violence. Against what? Things should work better damn it.

The projects that constitute “modern” life, and especially politics and so identity, are more fragile than they appear. For some reason, I’ve always known this in my gut. Maybe it’s the loneliness, or the aforemention pathos and rage, or my sense of history, whatever. My first book, City of Gold: An Apology for Global Capitalism in a Time of Discontent, argued that Hitler was the central figure in the modern political imagination, for which we attempted to construct a new political grammar (Bretton Woods, the European Project), but that resistance to Hitler alone, i.e., integrative capitalism, was itself a rather impoverished political life, sure to spawn widespread discontent, alienation. I’ve been wondering for some years (since the first Trump administration, actually) whether the post-war project was in principle doomed, or at least could have been sustained longer? At any rate, the idea of globalization, and even strong ideas of “Europe,” now seem hopelessly passe. Here is

, American Strong Gods: Trump and the End of the Long Twentieth Century.Later on, I tried to articulate a vital yet humane capitalism, and to take a sympathetic yet critical view of bureaucracy, at least in my own head. Not really sure what I’ve been trying to do, make peace with an idealized modernity or something, all of which now seems painfully, obviously, necessary — at least a generation ago. But I was right! We’ve created societies deened unworthy of loyalty, often deemed unworthy of propagation, breeding, and so doomed. So the critical intellectual in me, the “opposition” feels pretty good. Besides, there is mordant humor in watching critics of US hegemony gnashing their teeth at the abdication of US obligation. But “I told you so” is cold comfort for the loyalist in me. A lot will be destroyed. And of course it didn’t work. I’m not king, not sure I’m even a philosopher. And I still care about children.

It is not just the United States. For a German take, try

, Humpty Dumpty Had a Great Fall (“a change in political dispensation”) or pretty much anything recent by economic thinker . As you are probably aware, the German national elections are tomorrow. My guess is that the “firewall” against the AfD will hold for now. The Germans will form a government that will be paralyzed from its inception, and unable to confront German’s real problems. And political speech will continue to be criminalized, as German officials now openly admit: 60 Minutes on German Speech Controls. (It’s just rude when J.D. Vance says it.). Both those are just guesses, this morning. Other things are possible, and over time, are probable.I love Germany, but I think the German predicament is even more profound than that of the United States. Let me leave that for another day, maybe, along with assessments of the situation in other places. For now, it is enough to say that the world has changed in many countries. This appears to be the end of the twentieth century, that is, of the order that has structured my life from the beginning. I was born in Germany, my father stationed at Gelnhausen, militarily significant because situated on the “Fulda Gap,” the obvious pathway for Soviet tanks into Western Europe. That, we are told, is no longer an American problem. And, frankly, I know few Americans who would have any stomach for a war in Europe, or most places. Bleating on about Chamberlain (who?) won’t change that.

There will be reactions, I presume. Most revolutions are followed by restorations of some sort, but the restorations are never complete. The past cannot be escaped, but neither can it be recovered.

A part of me is in denial, of course. It’s only been a month since the inauguration; America is big and unruly and checks and balances to say nothing of governmental overreach — we won’t slide into fascism, and the Democrats will return, and maybe the NYT will be taken seriously again. Surely the situation in Europe is not that bad. Neither Putin nor Xi will live forever, and their people wish to prosper peacefully, love their children too, etc. All of which is true, more or less, but I don’t think it is enough. The narratives that sustained the Pax Americana, the liberal establishment, and the rest have been eaten away in various places, like a house beset by termites, or water flowing under glacial ice. See

, Euro-American Split: First Comments on a New World. The UN Plaza would make a fabulous mixed use development, great views across the East River to the hipster precincts of Brooklyn.None of which is meant to be despairing, which would be a sin. (Not to say I’m not guilty of it from time to time.) But life tends to reconstitute itself. It’s easy to forget how much death and destruction was wrought by the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Wars. It was hellish, madness — no good person would have wished for that. I doubt I would have had the stomach for it then, and I certainly do not now, sitting in a hotel room. Though we do what we must. But the Napoleonic Era was also a time of beginnings, as was the war with Hitler, a war with, in some senses, our 19th century versions of ourselves, raised to a pitch of organized insanity. (Read Ulysses S. Grant’s Memoirs for a sense of the absolute primacy of the nation.)

So, apart from restoration, how might we begin thinking about going forward? We are seeing some new shoots. For example, I’ve been heartened by a brilliant piece from

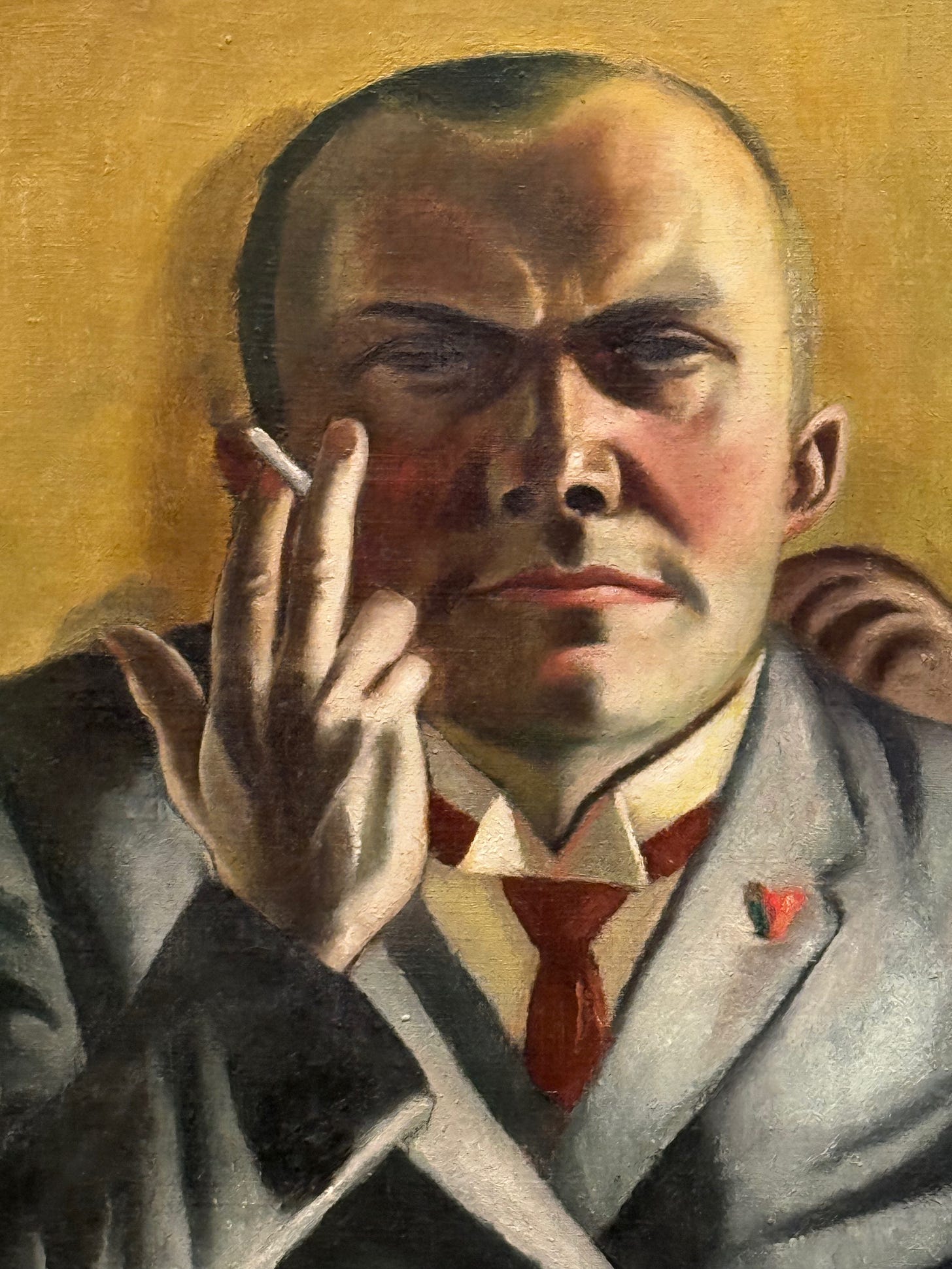

about renewal in our cultural life, and a more humane engagement with our technology, AI in particular, than that on offer by Musk & Co.: The Rise of the New Romanticism. Perhaps on point, the Met has a huge new show of Caspar David Friederich. We need something, and we will find it, and make it.

For many years now I have been working on a complex project, drawn from the company of friends, that has given rise to a forthcoming book: Social Thought from the Ruins: Quixote’s Dinner Party. Here is a draft of the introduction.

Introduction

One of the abiding wonders of art history, intellectual history generally, is how ways of living, thinking, and working come together, create a moment. Paris in 1905, for example. In time, for reasons sometimes clear but usually opaque, the moment passes, and it becomes difficult, even impossible to live, think, or work in that manner. The High Renaissance came to Italy and then went away, as Vasari noted more or less at the time, and Panofsky theorized several centuries later. Even while the past has never truly passed, accommodations will be made. People who experience such dissolutions often sense that they are losing a world, something that was and is now being felt to melt, becoming ever harder to articulate, as memories come to resemble dreams. And the sense of the emergence of what is next, the modern, often has a dreamlike quality, too, sometimes beguiling, sometimes terrifying.

It’s always hard to distinguish history in the making from one’s own biography, but I seem to have lived through such a moment, along with friends across the social sciences, between 2008 and 2020. The Global Financial Crisis, in 2008, caused the rich and powerful (especially rich) to question their ways of knowing. It was a great time to be doing political economy, to say the emperor has no clothes. I flew so much! Most of that came to an end in 2020, roughly speaking, when disease, a worsening migrant situation, and rising nationalisms literally and figuratively locked things down. But movement, especially transborder movement, had been central to globalization. The bien pensant had thought that borders were outmoded, but borders came back with a vengeance. Today, we in the social sciences don’t fly so much, and settle for Zoom, or just less contact, indeed less publishing.

The time in between the crash and the pandemic, however, was vivid, fragile, global. The colors seemed brighter, even at night. Academics might come to remember, meaning imagine, this time like a little Jazz Age, a time of myth and glamor, with undertones of utter violence. Certainly not the whole truth, but a truth, and maybe the most important truth, for now. The era had its ugliness, of course and as always, but maybe never before had such varied beauties been available to so many. This may have been the highwater mark of not just academic, but indeed haute bourgeois existence. For a certain kind of intellectual, anyway, there was much to love, even while grumbling about the Forever War and neoliberalism and general alienation. Those were years of wealth, movement and an inchoate sense of vulnerability, even dread of dangers unforeseen until articulated by the event. Everything was connected, everything was at risk. It was exciting. Yet there was also a pervasive sense that it couldn’t last, which proved to be true.

In those days, through a variety of scholarly projects, conversations, and endless emails, my friends and I triangulated among:

(i) the University that we long ago had enthusiastically joined;

(ii) key institutions of modern life, corporations, central banks, and above all the State, with its awesome powers of life and death, and its hordes of mandarins, the kind of people we trained; and

(iii) the public, the demos, that we all claimed to represent or serve in some way, and that our class claimed the authority to govern, the mandate of heaven because we were so smart.

As already suggested, even at its most glamorous, during Gatsby’s party as it were, this little Jazz Age was shadowed. Time went on, and especially as the pandemic hit, the shadows grew darker, as I presume you know if you are reading a book like this. The clouds on our intellectual horizons organized themselves into actual thunderheads, spawning lightning, even tornadoes. Mere ideas, discontents, words became political actions. Consider plagues, wars, civil wars, the reawakening of old hatreds, deaths of despair and vulnerable children who for reasons we cannot fathom fail to grow strong, to take their places in the world. The climate, both physical and social, changed and continues to change. Millions upon millions migrated. Ordinary life was routinely surveilled; a kind of authoritarianism came to seem normal. University life grew worse in obvious and subtle ways. Other powerful institutions also acted badly, or more often, just incompetently. The post-war international order frayed, to put it gently. People started talking about “polycrisis,” which might not have much analytic power but surely names a widespread sensibility. We will talk about crises in due course. People grew bitter. Very bitter.

Our history seemed to have entered its autumn. Fires burned pointlessly; the air was foul with smoke. Elsewhere, once welcome rain did not stop, until mountainsides slid into flooded valleys. Many people died one way or another. None of the old stories made sense. The few remaining artists had somehow lost much of their power, while audiences had lost their attention spans. Among these calamities, the University, my home, was transformed and I was no longer in love. Everyone seemed lost in dark woods, arguing about things they could not see, shouting at people far away.

Of course, Rome did not fall all at once, but the current widespread fascination with Rome bespeaks our own anxieties. And even after the city itself fell, “Rome” continued for centuries, in Constantinople, and differently in the West, and in some ways is with us still. But later ages could speak of the fall of Rome, just as we came to call 1914 the end of the long nineteenth century, and the suicide of Europe. Nowadays one hears intemperate talk that we are witnessing the end of the twentieth century order established in the wake of the World Wars, which increasingly look like one long war with halftime, as I said, Gatsby. Long held, seemingly permanent settlements in international affairs, in economics, in our institutional and social lives, and perhaps in our sentiments, have been swept away, gone with the wind as we Southerners say, like the Soviet Union. We shall come to know how to regard these days, but for the purposes of this book, let us think about what it would mean to work our way out of the ruins of the 20th century.

Long before people began to voice such anxieties out loud, you could feel something in the air. I was already disenchanted. Needing a ship, I joined a crew and we headed out, seeking new places, asking to be taught, and in our loneliness, trying to make new friends. But the pestilence was everywhere, families called and the money ran low, so we turned back, soon enough raising the ruins of the great library above the waves, glowing dully on the hill in the fading light. In my disenchantment, I tried to remember the poet: “Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey; without her you wouldn’t have set out.”

On our return, we found our houses, churches, roads, and of course schools all in need of repair, if not ruined outright. Our people gather in unhappy crowds. Still, not everything is given to us, each time is difficult in some way, and we do what we can. Sometimes we have chances to be useful in a manner befitting our age. Mostly we teach, listen and give counsel. On good days, we help very different sorts of people understand, even sympathize with, one another. There are joys. We meet with friends, have time to think, and many things to consider, even appreciate. There are glimmers of hope, always. It is a fine life. Yes, by now we know what these Ithakas mean.

The political and the individual, or if you wish, the social and the psychological, often mirror one another, Janus-faced. Janus is the Roman god of doors, thresholds. Inside and outside, past and future. Therefore, our social concerns may also be restated in personal, even existential terms:

(i) how to live as an intellectual concerned with the contemporary today (especially if being a professor is no longer an obvious answer);

(ii) how to study, think, and perhaps even help contemporary institutions (including the University but especially the bureaucratic State and its capacity for violence); and

(iii) how to express ourselves and reach others (the book and its alternatives).

This book is the wreck, the ribs and keel and maybe the ship’s log, and what can be salvaged?

But, said Robinson Crusoe, salvage is also material. How do we start building anew? What do we build, with what we still have?

* * *

After years of good intentions, I am finally reading di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, about the decline of the aristocracy in Italy, which seems timely. The book contains a famous line: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Strength and Hope and Wisdom, Pilgrims.

— David A. Westbrook