Greetings, Daughters and Sons,

Lightness of heart seems in short supply, and so perhaps worth considering. My doomscrolling tells me that we are confronting, at least and in no particular order, the imminent:

· end of the liberal international order, especially in trade, no in military affairs;

· breakdown of erotic possibility, not to say relations;

· failure of the old Constitution/constitution and dim hopes for a new one;

· dominance or failure of AI, so much AI;

· rise of autocracy;

· consolidation of managerial power and Nietzsche’s last man;

· collapse of the climate;

· poisoning by plastic

· and . . .

As a social critic, I have deeply pondered all of these issues, and feel a moral obligation to share my wisdom with you. :) Half of the texts I read, and an embarrassing portion of the pieces I write, declare themselves to stand at the pivot of history. Intellectuals tend to think of themselves as important individuals in significant times, I guess because they (alone!) can explain why the times are so important. I get it, have gone there myself, I’m not proud. But when did the tone become so relentlessly epochal? Since scholars and writers became largely irrelevant, and the model of the star journalist (often an apostate academic) came to dominate? Talk radio? Social media? Substack itself? Round up the usual suspects. Whatever. It’s all so breathless, repetitive, just exhausting.

What I am snarkily suggesting is aesthetic and so moral (if I wish to appear – be – like this, how should I comport myself?), not political. Let us stipulate that our situation is dire, unprecedentedly so. What stance are we to take? Enough with the Sturm und Drang. I’m not going in for a full-throated stoicism, but I am confident I can achieve a degree of sang froid, maybe even the cheerfulness that Nietzsche preached but rarely if ever achieved.

Besides, it is springtime. Mother’s Day. Time to think of regeneration, renewal, continuities. Not epochal breaks.

One might sensibly think that mothers, having made most of the world, do not need much further recognition. Yet we all work for roses, so let there be flowers. It’s the rest of us, however, who truly benefit from the day. Mother’s Day is a reminder, a chance to give thanks and, at least it ought to be, a salutary humbling. A chance to speak, a chance to remember.

I’ve been meaning to write about Caspar David Friedrich for some time, and this is a good day to do so. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had a big exhibit, which I saw a couple of times. CDF is one of my mother’s favorite artists, and her children gave her the catalog for Mother’s Day.

“Wanderer above a Sea of Clouds” (ca. 1818) is far and away CDF’s most famous painting, on a short list of paintings that have become images, endlessly reproduced. In my experience, such paintings, experienced directly, tend to feel very different from their reproductions. Wanderer, not so much, at least not at first glance, through the crowds of mostly young people photographing themselves and each other in front of an “icon” of Romanticism, youthful rebellion, etc. The painting hits pretty much like the poster, except, if you look closely, the suit is very dark green, not black, as I’d remembered without thinking about it.

But after learning more, looking more, and thinking more about CDF and his work, I began to see Wanderer differently. The Wanderer is a young man, but this is not a young man’s painting. CDF was in his forties, well married with children. He was a teacher, and was part of an artistic community. He had considerable renown. He was, as my students say, bougie. Wanderer is a Romantic work, par excellence, but CDF does not achieve the sublime, the sense of mystery and meaning, the pregnancy of his paintings through rebellion against convention, tradition, the ordinary business of humans trying to live among one another. CDF thus distinguishes himself from many Romantics, who attempt to achieve authenticity through opposition to manners, sociability, politics writ large — the rebellious tradition coming down from Rousseau and exemplified by, say, Byron.

The second thing I want to say about CDF is that the man could draw. Most great painters can draw, of course, demonstrate the structure of things, suggest distances, positions, and even dimensionality with mere lines and shading, which is impossible, when you think about it. But a few artists are doing something more. I think of Durer, Ingres, Picasso who said he wasn’t sure he was a painter but knew he was a great draughtsman, or something like that. Such artists make you see what, objectively, isn’t there.

I think CDF is in that class. The drawings were a revelation. I don’t think this can work on a computer screen, so to some extent you will have to trust me. But pencil and a wash, a monochromatic brown image, became landscape, with light, shadows, trees . . . colors that simply were not there.

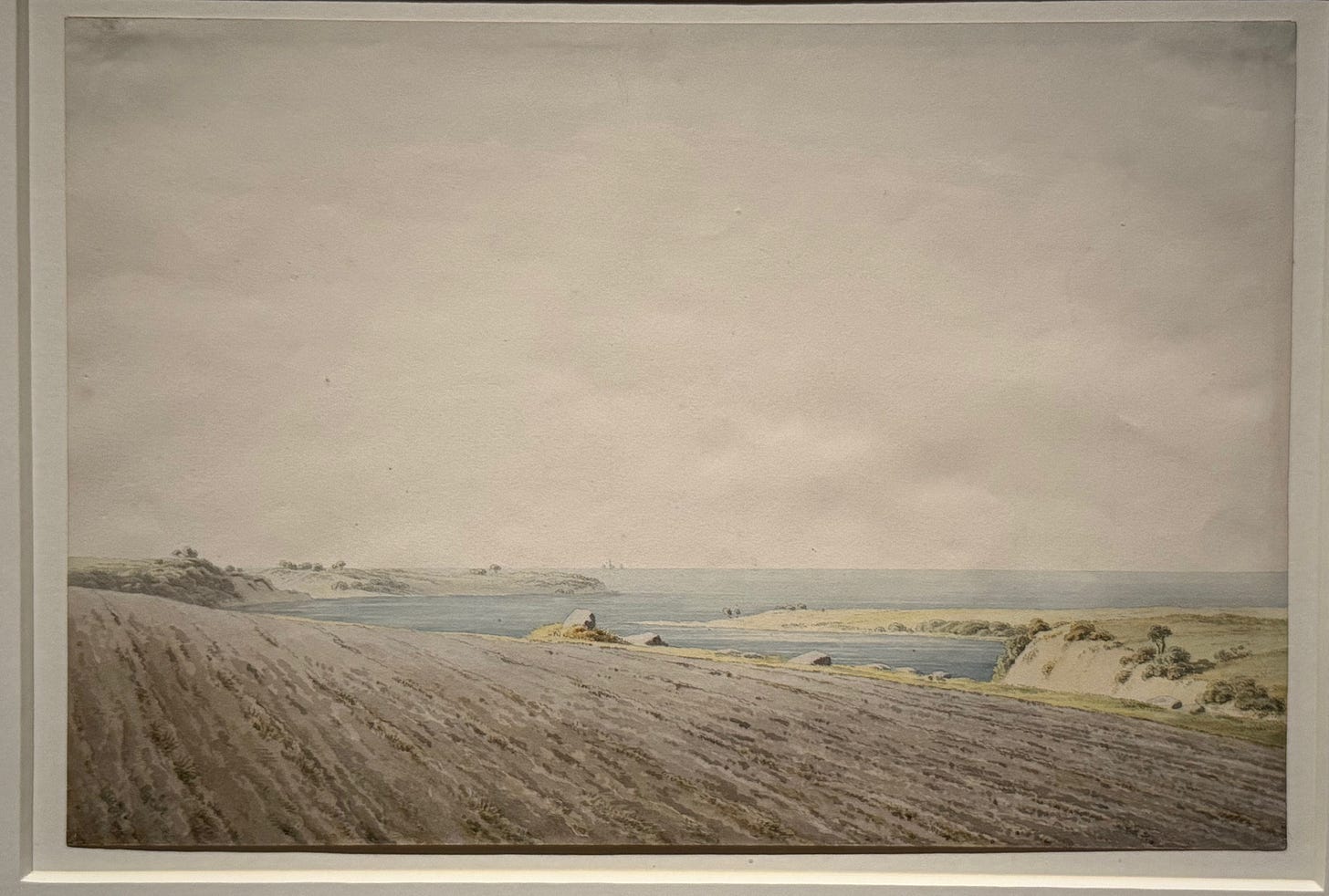

Brown ink and wash on wove paper. Later, CDF turns to color. But it’s not the big oils, the somewhat awkard mountains (CDF never saw the Alps), the allegories and the like, that really got my attention. It was the smaller watercolors, the disciplined subtlety. (See above re Sturm und Drang.)

As the rest of painting went in different directions in the course of the 19th century, CDF continued to pare down. The late works are beautiful, superficially simple, but so compressed, so conscious, as to be almost unbearable is not the right word . . .

Probably my favorite painting in the show. The screen only hints at its presence.

And I’ve used this image before, but it is Mother’s Day.

Shades of Vermeer. Presumably CDF’s wife Caroline. The Elbe flows from Dresden to Hamburg, and out past Blankenase. My mother’s family, and some of my youth.

We call this pond after her. At a tick over 4000 feet in Southern Appalachia, the leaves are just coming in. With little chlorophyll, there are hints of fall colors. The rhododendron and mountain laurel lining the banks are still weeks from blooming.

And in their eighties, they started growing orchids. Let there be flowers, indeed.

Happy Mother’s Day to us all.

– David A. Westbrook