A Soul No Faster Than a Camel

Magical, Real on the High Plains; Elk Moon; Siena in New York; A Writer’s Emancipation

Greetings, travelers,

Perhaps you’ve had your fill of electoral analysis? Wafer thin mint? Let’s talk of other things. Let’s talk of things seen and even unseen in the world, the feel of it, as opposed to viewed on screen.

My wife’s car broke many moons ago, a magic part lost its magic. The replacement was forged by dwarves under the mountains to the east of Salzburg, working on the 7th day of each month, as is traditional. When their work was done, the dwarves entrusted their treasure to Otar the Messenger, whose lineage is uncertain but some say he is half elf, others that he is somehow the offspring of a dragon and therefore can fly. Be such things as they may, traveling by windy ways at night, Otar brought the work, known to some as an “evaporator,” to the ancient cliff dwellings just west of Colorado Springs. There Otar hid the dwarves’ magic machine, amongst the red rocks and dark green pines, and I was told to bring the car.

That’s how I found myself rocketing across the high plains in her massive Mercedes turbo hybrid, instant torque, silly power, pretending I was a bullet train. But a bullet train without air conditioning or a dehumidifier. Normally the dogs and I are in a Subaru getting a little long in the tooth. That is, the car, one of the dogs, and me — the puppy is fine. Her car is much better for this. I’m playing.

An unusual amount of road kill. Shouldn’t somebody be picking it up? Are all those guys building roundabouts with the last of infrastructure money? Maybe the deer are just active, or trying to evade hunters. It is that time of year. Again I think how our commitment to the automobile leads so many to violent ends, and not just beasts of the field. For all my rural driving, I have yet to hit a deer, for which I’m grateful, as that’s a fear of mine.

A strong wind blows out of the south, rolling tumbleweeds straight across the westbound highway. Hitting a tumbleweed, in contrast, is no big deal. I was middle aged before I realized that tumbleweeds are actually pretty common, and really do tumble, sometimes astonishingly quickly.

The high plains have already gotten the first big winter storms, closing the interstate, maybe a little early. From the Colorado line onward, old snow, compacted, windblown, crusted. The road is dry.

I leave the interstate and cut across elevated open country, over 6,000 feet above sea level in places, higher than Denver, Colorado Springs, and the other cities huddled up against the foot of the Front Range of the Rockies. When I first started doing this drive the land was lonesome, high plains drifter, nobody will hear the shot. It’s still pretty lonely, but now there are windmills, so many windmills. Three dead pronghorn line the side of the road, which is unusual.

A town called Simla. Kipling wrote of the Indian hill town where the British went to escape the heat out upon the plains; somebody was reading about India when the town was founded. And from both Simlas, one can see high mountains. This Simla has a population of a few hundred, and is poor. Only the main drag is paved, and I slow the bullet train down to about 30. For some reason, wild turkeys have adopted Simla, and vice-a-versa. I spot two this time, pecking at the ground in front of a trailer. Like peacocks.

A few miles on, the radio says that several hundred antelope in Eastern Colorado died in the storm. The antelope winter on the plains, without shelter. When there is too much snow, they cannot graze. Deep snow also prevents them from crawling under fences. For some reason, antelope do not jump over fences, like deer, although they certainly have the power. As the snow deepened, the antelope moved onto the icy plowed roads and shoulders. Pronghorns are built to run, but not on asphalt, and so they slipped and were hit by cars and trucks, which generally cannot stop anyway. The radio says to drive slowly.

Pronghorn antelope are different from the antelope of the Old World, though they look very similar. Pedants insist on “pronghorns,” like they insist on “bison.” Anyway. I love them, strange as they are. The antelope, that is. They seem to be doing well, quite happy to live in sight of people, towns, even Colorado Springs, as long as they have room to run.

Early storms are a bitch. Some years ago, rain changed into a blizzard on the northern plains. Out on the range, the cattle hadn’t yet grown their winter coats. They got wet, and thousands froze to death, ruining ranchers. And years ago, in what was called the October Surprise, a snowstorm hit Buffalo while all the leaves were on the trees. Thousands of trees fell or were decapitated.

At Colorado Springs I am given an even more massive car as a loaner, perhaps in recognition of my patience. I head up into the mountains as darkness falls. Snow squalls, patches of wet some of which is ice, and the car is heavy and very expensive, making me nervous in the turns. Over the Pass and out onto South Park, which is a real place, an altiplano ringed by high mountains. I pass somebody, idly noting headlights, suddenly realizing that this isn’t the interstate, I’m on a two lane, I’m in the oncoming lane, and we are closing at maybe 160 mph. I get back in my lane. I’m losing focus.

Apparitions at speed: a bull elk with a magnificent rack is suddenly there, on the shoulder, just off my line of travel. He moves into the darkness, away from the road. A thing of beauty, a 700 pound ghost. I’m happy, for the sight and for his safety. I wouldn’t have been quick enough to miss him. It feels like a good omen.

The dirt road up the flank of the mountain has been plowed but my driveway has not. The big Mercedes slips and slides, and in a few places stops. I really don’t want to get this monster stuck. There’s enough of a pitch to back down and try again. Maybe the dwarves would make me a plow out of some magic metal. The wind has made a drift at the usual place, and it’s touch and go, but suddenly I’m over and onto the flat and into the garage.

The full moon rises, and casts light on the eastern slopes of the range to the west. This moon is supposed to be the “beaver moon,” when the beavers retreat into their lodges for the winter, swimming under the ice to retrieve stashed food. The creek below the house is called, unimaginatively, Beaver Creek, and is indeed full of beavers. The other names for creeks around here are “Trout” and “Crooked.” Anything else is a sign of frontier genius. Beavers are cool, but I think this is the elk moon.

I’ve heard it said or maybe I read somewhere that there is an Arab proverb, and one can find similar things online so it must be true in a way, to the effect that a man’s soul travels at the speed of a camel, or perhaps no faster and yet . . . less than 36 hours later I found myself speeding in a different direction across South Park with the sun rising and the peaks shining. I have an alumni relations dinner in New York, at a literary club that counts Mark Twain as an early member, currently housed in an old Vanderbilt townhouse on the upper East Side. Got to get to airport, DEN to LGA, cab to dinner, early enough to change in the bathroom. Not sure where my soul is. He’ll catch up.

I pull out to pass a big truck, and for just an instant, see a wonder. A large herd of elk has come across the Park and is up against the fence. The elk winter out in the Park, along with the pronghorns. The low sun – the light is fantastic! – hits their coffee and fawn bodies, I can see their eyes – they are feet away – and I’m flying. I hit the first ranch road I can, braking hard to do so, pulling off, turning around, the trucker honking at me, presumably furious, maybe he does not care for things of beauty you don’t see many times in your life even if you are lucky. By the time I get back and situate the car, the elk have moved back out into the Park and, worse, into the sun. So I didn’t capture the wonder I saw, and this is the picture that I did get.

Dinner was lovely, good to see colleagues, progress was made, and I ended up in a quiet dark club with a liquor library and excellent live music. A former student now friend remembered he kept a bottle there, hard by my usual hotel. So we drank very good bourbon and talked about life, education, children. Yes, progress, or at least the passage of time, and in a good way – which is not something a middle aged guy gets to say all that often.

Hotel staff recognizes me by name when I check out, even though I’ve not been here in 18 months or so, which is touching. Not Hemingway at the Hotel de Crillon or whatever, but not nothing.

I am abruptly re-mindful that I’m writing in public. To my New York City friends, my apologies. I miss you and hope we see one another soon and catch up. But that is not this trip. Press on.

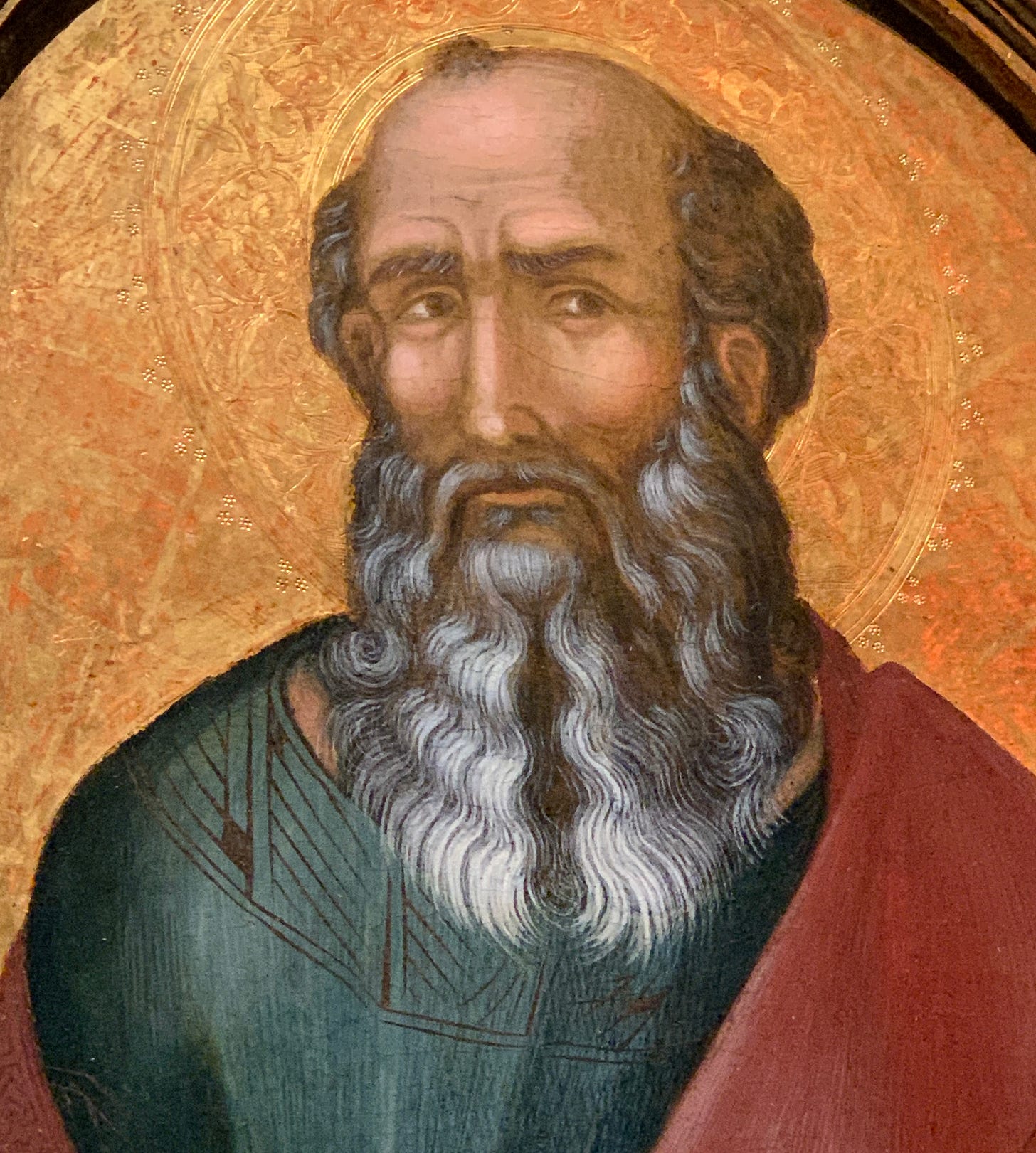

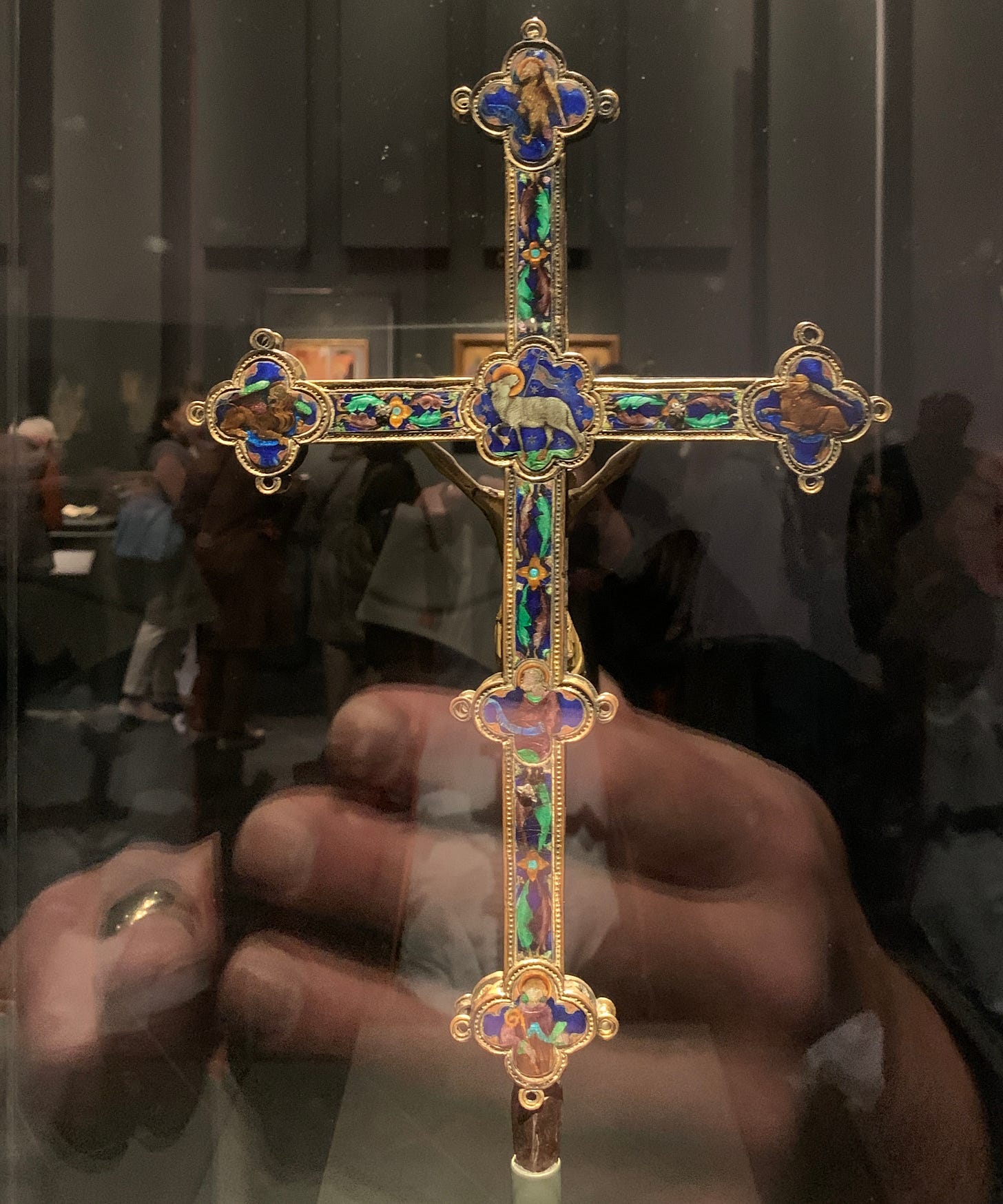

I have time to see an exhibit, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. From there to the airport. For a few decades, artists in Siena took ideas from Rome and over the Alps, mostly Paris, and were influenced by Byzantium and even textiles from out on the steppe of central Asia, and created a unique and powerful style. It was a moment. And then half the city, and its artists, died in the Black Death, and the moment passed. In this unprecedented show, the Met brought together works in a number of museums, and churches in Italy, to synthesize and express the moment. NYT on Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350

At the top of the famous broad stairs, where people are always eating, pigeons are being pigeons, and schoolkids are taking class photographs, I am stopped by a guard. The Met does not check luggage, not even rollerboards. What I am to do, I ask? She says, talk to the guy in the hot dog truck at the foot of the stairs. Really? I say. I wouldn’t tell you if it weren’t true, she says. The hotdog vendor says twenty dollars and I’ll hold it. Be back before 5:00. I tell him I have a plane. He again says be back by 5:00. Ah, NYC. But I have always relied on strangers, if not always their kindness.

The show was deeply moving, and very difficult – for all my time spent looking, reading, and talking about painting over a few generations now, when I shut out the voices and focus I feel, acutely, that there is much I can say but so much I do not truly understand. This used to bother me. What follows are a few thoughts, nothing like an interpretation.

Sometimes one has to see art live. To use the cliché, the pictures do not do the work justice. Pictures of art, and especially pictures on screens, emphasize formal composition, but at the cost of texture, depth of color, and above all, delicacy. Many of these paintings and objects were small, “devotional,” designed to be used by individual, up close, for prayer and contemplation. The lines are often no thicker than a hair. Color is built up imperceptibly. The works are devotional in another sense: their creation is an act of devotion, at least to craft, perhaps to “art,” however that may have been thought, and to God, too.

Most of the paintings are tempera on wood with gold leaf. The colors, in a darkened gallery across an ocean and over 700 years later, glow. Even illuminated manuscripts look like they were drawn yesterday. But some things have been lost, or damaged in this way or that, often wars. Time, permanence, works, and what remains?

These paintings were done without linear perspective. For centuries, perspective has been seen as decisive: three dimensional space could be represented on a two dimensional plane. For some people, such representation – the tension between two and three dimensions – defined painting, and certainly defined the transition from what we call “medieval” to “modern” European painting. (The denial of single point perspective in late 19th and early 20th century European painting required a new kind of “modern.”) Art historians, and so amateurs like me, tend to care about such things. Probably too much.

But the Sienese works, done roughly 200 years before the discovery or at least formalization of linear perspective, do not work like later renaissance paintings. They are not just “flat.” They are frontal. In your face.

I understand “iconic” better now. Sure, the viewer is meant to venerate the image of the Madonna and Child, or the Deposition (taking Christ down from the Cross) or what have you. But the energy flows in the other direction, too, from the image to the viewer. The works are authoritative, powerful, as we say nowadays, interactive. Hence the gold, the color, the luminosity.

In our image rich environment, art still holds onto the ghost of its secularized yet sacred status, though its significance in the world has been in a gentle decline for at least a century. Worth discussion. But still, even now, one “should” care. And art remains a token of real wealth, of course, that’s not new, but that, too, springs from some notion that this object, unlike most, is important. Matters. And therefore is valuable.

In its strangeness, however, the Sienese work confronts us with the idea that there are very different ways, perhaps more serious ways, to make and experience art that are largely, perhaps entirely, inaccessible to us. We are as constrained by our world as they were by theirs. I am reminded of cave drawings. And yet . . . I’ll stop here. See it if you can.

Airport, dinner in lounge, flight, try to work, a few hours of mountain driving, beyond tired now, about to turn off the highway, and the elk are up against the fence, feet away, sharp in the headlights. I turn the car, drive back, they move off a bit, of course, the phone isn’t the “right” tool. This is a bad picture, yet I love the painterly effect. The mystery. Feels right.

The Emancipation of the Writer?

Out of the blue, my buddy Ali Khan sent me the following. He said he was thinking of me when he wrote it.

Sevens – Writer Emancipation

1. The writer starts by flying in a cage. The cage demands submission to grammar, punctuation, style, genre, clarity, readers, critics, editors, agents and publishers.

2. Many writers, like attorneys, judges, bureaucrats, and others, must die in the cage, happily, unhappily, as les miserables. Some die for a compliment, and some for a semicolon.

3. Emancipation begins with an intense awareness that every cage iron bruises imagination, creativity, and originality.

4. Seeking emancipation, the writer first throws out all critics from the cage, making more room to fly.

5. Next comes throwing away genre, punctuation, grammar, and style, one at a time but in no particular order.

6. Finally, the writer kicks out the agent, publisher, editors, and obsession with intelligibility. Emancipation nears completion.

7. The cage flings open to fly out write whatever you please as you please willfully iconoclastically Nietzsche could not cope with sovereignty and lost his mind.

(© Legal Scholar Academy, reprinted with permission.)

Hilarious, and a little frightening. So nervous laughter. Thanks Ali.

Safe travels. Don’t forget to give your soul time to catch up.

— David A. Westbrook

Post Script

Many of you receive Intermittent Signal as an email, and often on your phone. While I am delighted to be read in any format, both text and especially images look much better on the platform itself, and on a computer rather than a phone.

There is a lot to like on Substack, and the vast majority is free. I sometimes feel like a teenage boy at an all you can eat buffet.

If you have taken out a paid subscription, thank you. It really does mean a lot.

Whether or not you become a paying subscriber, I am trying to build audience, so please do share my work with anybody who might be interested.

We moved to Colorado Springs 16 years ago, and I am STILL obsessed with pronghorns. They are my favorite Colorado animal!

I kinda like following you around your world, a bit of which is mine as well …